Víctor Espinola: “It would be a beautiful project if I could collaborate with Kurdish artists.”

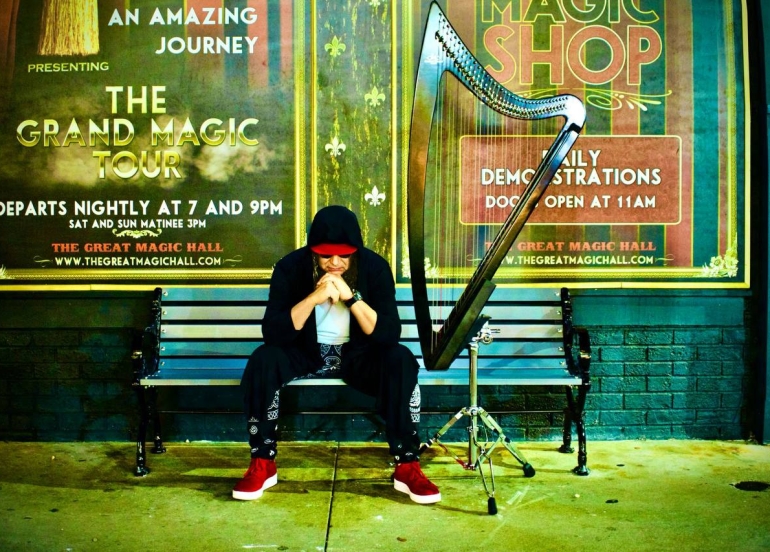

Víctor Espinola, the internationally acclaimed Paraguayan harpist, singer, and composer, is widely recognized for redefining the boundaries of the Paraguayan harp. His music fuses flamenco, Brazilian samba, Latin American rhythms, and tonalities from the Middle East and Africa, creating a style that is unmistakably his own. Having traveled and performed in countries across South America and Europe—including Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, and Germany—Espinola gained international stardom through his legendary collaborations with Yanni, where he captivated millions with his passionate, electrifying performances. In this exclusive interview, conducted by Gulan, Espinola discusses his artistic origins, technical philosophy, his transformative years working with Yanni, and his admiration for the Kurdish people.

Gulan: How did your interest in the harp first begin, and what drew you to this ancient instrument?

Espinola:My relationship with the harp didn’t begin academically—it began emotionally. The first time I heard the harp, its sound felt ancient, almost otherworldly. I didn’t know anything about its history at that moment; I simply felt an intimate, spiritual pull toward it. I realized that the harp had a unique way of carrying emotion—pure, unfiltered energy.

That initial connection eventually led me to explore its origins. Only later did I discover the vast and rich history behind the instrument, stretching across continents and civilizations. Understanding this made my connection to the harp even deeper. It felt as though I was joining a lineage that was thousands of years old.

Gulan: In your view, which cultures or civilizations have had the greatest impact on the development of the harp as we know it today?

Espinola: Many cultures shaped the harp. Ancient Egypt was one of the earliest civilizations to use the harp in ceremonial and cultural contexts. Mesopotamia also contributed to its development through early stringed designs. Then you have the Celtic traditions, which introduced what many people today imagine when they picture a harp.

And in Latin America—and especially in Paraguay—the harp evolved further. The Paraguayan harp has its own structure, timbre, and rhythmic personality. For me personally, those Paraguayan roots are central. They shape the way I play, the emotional power I try to bring, and the rhythmic language that comes naturally to me. Each culture gave the harp something unique, and today the instrument carries pieces of all those histories.

Gulan: How do you see the harp’s role in contemporary music compared to its historical position?

Espinola: Historically, the harp had a sacred status. It was associated with royalty, religious ceremonies, and classical music. It was viewed almost as a divine instrument—something pure, delicate, even untouchable.

But today, the harp is breaking out of those limitations. In modern music, the harp can be bold, percussive, daring, and experimental. It can be electric, amplified, rhythmic, cinematic—you name it. I see this evolution as essential. It shows that the harp is not a relic; it is a living instrument capable of adapting and transforming with the times. It is still mystical, yes—but now it can also be fierce.

Gulan: Was there a particular moment that inspired you to learn the harp?

Espinola: Yes. There was a moment when I realized that the harp could “sing” in a way that went beyond classical expectations. I started experimenting—changing rhythms, hand positions, and the natural articulations of the sound. It felt like discovering a new language.

At that moment, I stopped viewing the harp as an instrument and began seeing it as a voice. A voice that could express emotions I didn’t have words for. That realization changed everything and pushed me to commit to the harp with all my heart.

Gulan: What challenges did you face when learning to play the harp, and how did you overcome them?

Espinola: The harp is physically demanding. You need strength, coordination, and precision. But the biggest challenge for me wasn’t physical—it was artistic. I wanted to play genres and rhythms that were not commonly associated with the harp. There weren’t many models or teachers who were doing what I envisioned.

So the challenge was internal: trusting myself, believing in my own musical instincts, and daring to create something new. Through patience, exploration, and self-confidence, I learned to embrace my own path instead of following a pre-existing one.

Gulan: Was there any harpist who inspired you at the beginning of your journey?

Espinola: No, not at first. I was much more influenced by percussionists and rhythmic musicians. Rhythm is my natural foundation. I think that’s why my harp-playing developed such an energetic and percussive identity.

Gulan: Harps are delicate instruments. What is important for maintaining them, especially under non-standard conditions?

Espinola: Weather is the biggest enemy—humidity, temperature changes, sunlight. I always travel with spare strings for every harp I use. I monitor humidity levels constantly.

When it comes to the wood, especially in older harps, it must be protected from direct sunlight and sudden temperature shifts. If I’m traveling or the weather changes dramatically, I let the harp rest before packing it. You can’t rush these instruments. Their wood needs time to adjust.

Gulan: How often do you change your strings, and which type do you prefer?

Espinola: It depends on how much I’m playing. The strings I use the most get replaced every few months. High-tension strings break faster. On my Paraguayan harp, I use nylon strings because they give a warm, rhythmic tone. For other pieces, I experiment with custom blends depending on the color of sound I’m trying to achieve.

Gulan: Do you have any rituals before or after playing the harp?

Espinola: Before performing, I like a few minutes of silence—not meditation, just a quiet moment to center myself. After performing, I gently wipe the strings and wood to remove sweat or oils. I treat the harp with respect. It’s not a tool—it’s a partner, a voice, a companion.

Gulan: Your work with Yanni is internationally recognized. What was that experience like?

Espinola: Transformative. Working with Yanni changed my life. He allowed me to express my full musical identity without limitations. He never asked me to tone anything down. In fact, he encouraged more energy, more passion, more freedom.

From him, I learned how to shape emotional journeys in music. Yanni is a master storyteller in sound. He understands how to build intensity, how to guide emotion, and how to connect directly with the audience’s heart.

Gulan: How did Yanni influence your harp style and compositions?

Espinola: He helped me see that the harp could be cinematic—epic even. Playing with him expanded my perspective. I began composing with story arcs in mind, rather than just melodies. I started thinking in terms of emotional landscapes.

Gulan: Do you have any unforgettable memories with Yanni?

Espinola: Many. One I’ll never forget was our concert in Yerevan. During the performance, Yanni turned to me, gave me a nod, and his expression said, “Go for it.” That moment of trust, in front of thousands of people, was unforgettable.

Recording in the studio with him was also eye-opening. Hearing how my harp blended into his arrangements taught me how universal the harp can be.

Gulan: What is the most beautiful piece you’ve played on the piano?

Espinola: “Felicia.” It is pure emotion—raw, honest, unpolished. Technically, it’s not the most complicated piece, but emotionally, it demands complete sincerity. You can’t cheat with a piece like that. It humbles me.

Gulan: How does being both a harpist and a pianist affect your musical perspective?

Espinola: A harpist listens to the silence between the notes. A pianist listens to the structure, the harmony. Together, they expanded my emotional and technical range. But the greatest lesson I’ve learned is that depth is more important than speed. Emotion is more important than complexity.

Gulan: Do you compose your own harp pieces? What themes guide your compositions?

Espinola: Yes, I compose all the time. My compositions focus on rhythm, emotion, and contrast. I blend Latin American textures, Eastern scales, and cinematic rises and falls. I want my listeners to feel as though they’ve taken a journey—even if they don’t know where that journey leads.

Gulan: What advice would you give to someone who wants to master the harp?

Espinola: Respect the instrument, but also challenge it. Learn the technique thoroughly—but don’t remain confined by it. Let your cultural background, your personal history, and your instincts shape your sound. And above all, be patient. The harp doesn’t reveal itself quickly. It teaches slowly.

Gulan: In which music genre does the harp shine the most?

Espinola: The harp shines wherever emotion is needed. For me, that’s world music and contemporary fusion. But it can be breathtaking in classical, jazz, pop—any genre. Its adaptability is its greatest strength.

Gulan: What do you envision for the harp in the future?

Espinola: I’m currently working on a solo album that blends the harp with electronic elements and traditional instruments from South America, the Middle East, and Asia. My dream is to show the harp as a universal storyteller—one capable of crossing borders, cultures, and languages.

Gulan: Finally, what do you know about the Kurdish people?

Espinola: The Kurds are descendants of ancient Indo-Iranian tribes, with a history stretching back thousands of years. They are the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East and are known for their rich culture, remarkable cuisine, and powerful music.

I would absolutely love to collaborate with Kurdish artists. Their musical heritage is profound and emotional. It would be a beautiful, inspiring project—one I hope I can bring to life someday.