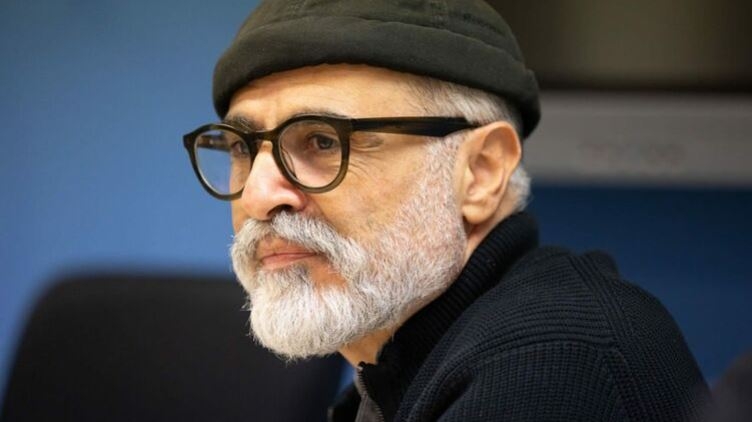

Sharam Khosravi to Gulan: “Borders Are Human Creations That Produce Fear, Inequality, and Global Apartheid”

Sharam Khosravi is Professor of Social Anthropology at Stockholm University and one of the leading scholars in the field of Critical Border Studies. His work focuses on borders, migration, displacement, and everyday experiences of state power, with particular attention to the Middle East, Europe, and the lived realities of people on the move. Professor Khosravi’s research combines ethnography, political anthropology, and critical theory, and his writing has played a key role in reframing borders not as static lines on maps but as social processes that shape identity, mobility, and inequality. He is widely recognized for his critical engagement with migration regimes, nationalism, and global hierarchies of movement.

Gulan Media: In your work, you often describe borders not simply as lines on a map, but as ongoing processes that shape people’s everyday lives. When we look at the Middle East, particularly borders created through colonial arrangements such as Sykes Picot, how should we understand their role today? Have these borders become socially accepted over time, or do they still feel imposed for many of the people living with them?

Sharam Khosravi: Borders are fictive in the sense that they do not come from nature. They are constructed by human beings. They are social constructions and products of history, particularly the colonial projects you mentioned. At the same time, we should not forget that borders have very real consequences. They deeply affect people’s lives and create many problems. In that sense, they are real.

It is also important not to think of borders as fixed lines. Borders shape how we think about geography and about people. They create imaginations of difference, where people are seen as fundamentally different depending on which side of a border they live on. When I talk about borders, I am referring to modern borders that emerged with the nation state system.

Before this, the Middle East was organized differently. The Ottoman and Persian Empires had forms of territorial division, but these were not borders between nation states. It is therefore important to distinguish between historical forms of borders and modern borders.

Gulan Media: Across the region, borders are becoming increasingly militarized, particularly between Iraq and Turkey, Iran, and along the Syrian border. From your perspective, what does this growing fortification mean for everyday life in border regions, especially in places such as Kurdistan?

Sharam Khosravi: This militarization is something we see globally. We see it between the United States and Mexico, in the Mediterranean, and across Europe. We also see it clearly in the Middle East. Iran is militarizing its border with Afghanistan, and Turkey is building walls along its borders.

Kurdish people are particularly affected by this process. They are caught between multiple nation states that are militarizing their borders, and they pay a very high price every day. These borders divide Kurdish people into different political entities. Many people living in border regions must cross borders simply to survive, carrying goods on their backs and risking their lives daily.

Minorities who live along borders always suffer the most. Kurdish people, Baluch people on the Iran Pakistan border, and others experience the tragic consequences of decisions made in capitals such as Tehran, Baghdad, or Ankara.

Gulan Media: Supporters of border fortification often argue that militarization brings security. From your perspective, does this process create security, or does it generate something else entirely?

Sharam Khosravi: It creates fear, not security. For example, the European Union created Frontex in 2004 with a very small budget. Today, its budget exceeds nine hundred million euros, and it operates drones, satellites, helicopters, and ships. Yet European borders are not more secure. People still arrive, and people still die in the Mediterranean.

This type of militarization also creates a strong market for human smuggling. It is not a sign of strength but a sign of weakness. When states fail to manage migration in a humane way, they respond by building walls, increasing violence, and criminalizing movement. No wall can stop people who are forced to flee.

Gulan Media: We are seeing large waves of migration from the Kurdistan Region, particularly among young people, even though the region is relatively stable. Do you see this primarily as an economic issue, or is it more closely connected to what you describe as stolen time and a sense that the future is blocked?

Sharam Khosravi: Migration is never caused by a single factor. It is always a combination. Economic conditions matter, but so does the question of the future. Even when people have financial security, they still think about what kind of future awaits them or their children.

The Middle East is a region constantly threatened by war, conflict, and instability. Even in relatively safe places, people feel that the future is fragile. When young people do not see a future where they live, they try to find it somewhere else. Europe and North America are imagined as places of safety and stability.

Gulan Media: Iraq and the Kurdistan Region host large numbers of internally displaced people. Do internal checkpoints and administrative boundaries between Erbil and Baghdad begin to function like international borders, producing separation and a sense of us versus them?

Sharam Khosravi: Yes. Borders are not only international. They also exist internally through checkpoints and administrative boundaries. All borders send signals. They shape imagination and create meaning. When you build a wall or a checkpoint, you send a message to your neighbor that they do not belong and that they are different.

Over time, these internal borders create distance, hostility, and negative feelings between people.

Gulan Media: Do these internal boundaries harden identities over time, even within a single country?

Sharam Khosravi: Yes, absolutely. Borders are manifestations of nationalism and state sovereignty. They are closely linked to national identity. Education systems reinforce this through maps and territorial imagination. These symbolic boundaries play an important role in shaping how people understand who belongs and who does not.

Gulan Media: You have argued that borders do not simply divide land, but actively produce identities. For Kurds who are divided across four states, how have borders reshaped Kurdish culture, language, and political life?

Sharam Khosravi: When nation states are created, they promote a national language and culture. Other languages and cultures become marginalized. Kurdish language and culture are shaped differently in each state.

At the same time, we must ask difficult questions. If a Kurdish nation state were created, who would become the minority within it? There is not one single Kurdish culture. There are different languages, religions, and traditions. Any political project must seriously address this internal diversity, or it risks reproducing the same problems we see today.

Gulan Media: European powers played a major role in shaping instability in the Middle East, yet today Europe is closing its borders more tightly. Would you describe this situation as a form of global apartheid?

Sharam Khosravi: Yes, absolutely. This is global apartheid. A Swedish or Norwegian passport allows travel to a lot of countries without a visa. An Afghan or Bangladeshi passport allows travel to only a few dozen. Mobility is directly linked to economic opportunity.

This creates a global hierarchy of movement. Some people are allowed to move freely, while others are restricted. This system reinforces inequality and class divisions on a global scale.

Gulan Media: How do you respond to European arguments that migration damages security or overwhelms capacity?

Sharam Khosravi: This argument is false. Wars carried out by the United States and Europe have displaced tens of millions of people. These interventions are the source of insecurity, not migrants. Migrants are people trying to survive the consequences of war, occupation, and exploitation.

Gulan Media: From the perspective of Critical Border Studies, is imagining open or reimagined borders merely an ethical or poetic idea, or can it realistically become a political project for peace in a conflict ridden region like the Middle East?

Sharam Khosravi: Borders are human creations. They did not come from nature or from God. What has been created can be recreated. However, removing borders immediately would not solve existing problems.

What is essential is protecting both the right to migrate and the right to stay. People do not want to be migrants. Kurds want to live in Kurdistan, Palestinians want to live in Gaza. Migration is forced by war, poverty, and exploitation.

Borders today exist for poor people, not for Western armies or the wealthy. A truly humane future requires moving beyond the nation state system that divides people into rigid categories.